Why Puppet/Chef/Ansible aren't good enough (and we can do better)

This particular blog post was sitting on my mind for a long time. I don't want to start a flame war, but at the same time I also don't wish for Linux community to build and grow upon ad-hoc solutions that we've accumulated over the last 30 years to the packaging and deployment problems.

History of Linux automation

Remember (old-timer?) Linux user typing commands into terminal that goes and mutates the state of the Linux machine. They'll go and stop a process, change configuration file and start the process again. They're the one connecting to the machine and making sure the state of the Linux machine is mutated correctly. Let's call this method Imperative Configuration.

They'll soon realize there are many routine tasks and there is a benefit of automating them. In old days they'd write a collection of bash scripts, but today we have frameworks in most popular languages to refactor imperative steps and reuse them. Let's call this method Automated Imperative Configuration (as implemented for example in Chef (Ruby) or Fabric (Python)).

Code complexity and the need of a documented operating system soon inspired our Linux user to think further. What if they built one layer of abstraction on top of those steps and rather describe the end state of the system we'd like the Linux machine to be and the underlying system will take care of examining state and executing commands to do so? Something like we use SQL everyday, to focus on WHAT instead of HOW. Let's call this method Declarative Configuration (as implemented for example in Puppet and Ansible)

Taking declarative configuration to the next level

However, there is one huge, seriously huge penalty due to our new abstraction layer. Even more code complexity hidden below the declarative configuration statement someone needed write. Let me explain.

Take for example a simple declarative statement:

Package named nginx should be installed on the system.

Our tool needs to figure out

- what kind of package manager we're using on our Linux distribution

- check if package is installed

- if not go ahead and install it.

There were three steps needed to accomplish such task. The problematic part of such system is the fact our tool had to connect to the machine and examine all of the edge cases that machine state could be in and decide based on the state what imperative tasks to execute. Let's call this method stateful declarative configuration.

Trivial example shown above does not demonstrate how number of combinations of machine states grows exponentially once a decent amount of services interoperate on a Linux machine. Many edge cases our code below delaractive configuration has to cover. Anyone developing Puppet/Chef recipes will be able to explain you this phenomenon in practice.

Going stateless

What if we design our declarative configuration model to be stateless? This would greatly reduce complexity, amounts of code written and at the same time also make it way simpler to explain how different components are written.

Before we dive into that, let's see another real world example of stateful vs. stateless solutions to the following problem:

Securely verify email address of a user registered on a website.

Stateful solution

- Generate a random key (cryptographically random, so it can not be guessed)

- Store the key in our database

- Send email to the user with a link to our website containing the key

- Once user has clicked the link in the email, check the random key matches the one in database and hence we know they have gotten the email

- Remove the key from the database

Stateless solution

- Take email of the user and sign it cryptographically

- Send email to the user with the link to our website containing the signature

- Once user has clicked the link in the email, verify digital signature and if it's valid, we confirm his email

Our stateless solution did not require a database to keep the state. Actually all the state is transfered over the network, so you could say network is our database or that we don't have any state.

Less work (eg. designing database schemas, extra code), less edge cases you can stumble upon (eg. database migrations).

Stateless solution does require us to be clever. Since there is no state, we have to send over any information we might need for example user registration date. If we used a database, we'd store datetime of registration of the user. In our stateless solution we could use a JSON string with email of the user and his datetime for registration and sign that. Even if we decide to change timespan of when is the registration still valid, we have all the information we need inside our JSON and its signature.

For more about this solution see My Favorite Database is the Network.

Current de-facto standard of stateful packaging

Obviously I'm heading to the idea of packaging software and configuring Linux machines (or any other operating system) statelessly. Let's call it stateless declarative configuration.

Stateless configuration is a consequence of good design of a system (as we have seen for the trivial example of validating email addresses for a website).

I'm not going to propose how to design such operating system to be stateless, because Eelco Dolstra (with two co-authors) already did for us in a scientific paper and we can use such linux distribution with all the benefits of the clean design today.

I will instead summarize (part of) the NixOS Linux distribution design (do read the paper, it's small and slowly explains the motivation and the design) to achieve stateless configuration.

Grab a coffee/tea, relax, get ready.

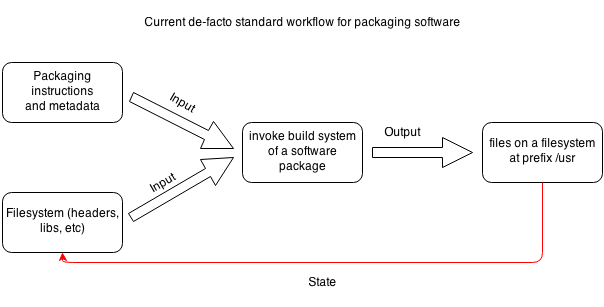

If you think about how packages are installed on a Linux distribution it's summed up in the following diagram:

Notice that output files of one software package are also inputs (as the filesystem) to the other software packages.

That's our state. Filesystem is our primitive, hierarchical database that's making our solutions complex and non-deterministic.

/usr could be represented as a table in our database and package does lookups by filename inside

/usr/lib, /usr/include and so on. Contents inside those directories will affect our building results. What's worse,

building systems will look into other directories such as /usr/local/ or /opt to determine packaging requirement files.

In case you still don't believe me this method goes soon out of control, read this.

Packaging going stateless

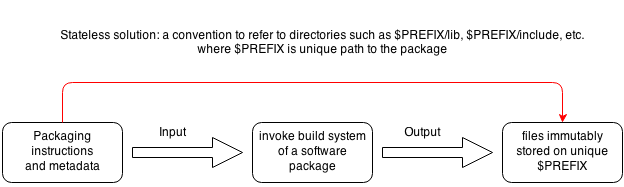

Removing our filesystem as a state we get the following workflow:

We've changed only one thing:

Output files of a successful build are stored under unique $PREFIX directory, so as long as we can map the package name from packaging

metadata to its $PREFIX, we can deterministically say headers in $PREFIX/include belong to that specific package.

No more global prefixes such as /usr, /usr/local, /opt from FHS. Software which doesn't assume

too much about their prefix will still just work.

Building systems out in the wild also work with unique $PREFIXes. Just pass C_INCLUDE_PATH=$GCC_PREFIX/include:$MYLIB_PREFIX/include,

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=$GCC_PREFIX/lib:$MYLIB_PREFIX/lib (and so on) environment variables to the package we're building collected from dependency tree we have in our packaging

metadata.

Beyond stateless design

While we're at rethinking packaging, let's go for deterministic builds. Packaging output should depend only on packaging instructions we've written.

Actually all that said, we have to carefully pick a language to specify packaging instructions in it.

Our package manager is implemented as a Purely Functional Language.

Pure function is a function without side-effects. Output only depends on the input of the function, nothing else should affect it's output. If it does, it's a bug in

the implementation of the language. For example random() is not a pure function, since it takes no input and returns a different results for the same input.

By choosing such a language we make sure it's not possible to introduce any state inside our packaging instructions.

Our package manager is called Nix. Nix tries very hard to be deterministic. It stores all build packages at unique prefix and mounts them as read-only to ensure nothing will change the output of the building process once it's done.

It goes as far as changing timestamps from all files inside the prefix to unixtime + 1. Time is a side effect of our build, since two sequential runs should return same result. Term coined to describe packages built with no side-effects is Purity.

Features as a consequence of stateless design

-

Deterministic. Removing stateful filesystem greatly improves determinism. We've solved the same problem at language level by choosing appropriate language. Our builds are deterministic based on our input of packaging instructions (what are dependencies, source tarball, etc)

-

Rollbacks. No state means we can travel through time. Execute

--rollbackor choose a recent configuration set in GRUB -

No dependency hell. Packages stored at unique $PREFIX means two packages can depend on two different

opensslversions without any problem. It's just about the dependency graph now. -

Source and Binary best of two worlds. Since we hash all of our inputs to the building process, we can uniquely identify our build. Before build from source is preformed, we can ask our build farm to give us a binary package for the hash (so called substitute for the build). If no hash matches, build from source.

-

Multiple environments. To generate working bash environment with all the declared tool available, we have to symlink them together. Going further, we can create different environments with different collection of software.

-

Multi user. Besides system environment, each user gets it's own environment to install software

-

Atomic. Your system is activated once final symlink is pointed to your system environment. Symlink is an atomic operation on Linux. No more inconsistent states because of power outages.

-

Build farm. Build binary packages based on the changes in git repository, run tests and release it.

-

Provisioning (sysops ready). Provision

EC2,HetznerorVirtualBoxand configure it.

Often developers would say package managers we use nowadays could adopt this philosophy. I agree, but they would have to be completely re-designed and keeping backwards compatiblity would be of a great challange, if not just impossible.

Stateless declarative configuration

Expanding the idea to configuration management is then trivial based on clever design of Nix package manager. Configuration files

are just a simplification of a software package. Packaging instructions generate the configuration file. Following is packaging

instructions written in Nix to describe a systemd nginx service.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | systemd.services.nginx = { description = "Nginx Web Server"; after = [ "network.target" ]; wantedBy = [ "multi-user.target" ]; path = [ nginx ]; preStart = '' mkdir -p ${cfg.stateDir}/logs chown -R ${cfg.user}:${cfg.group} ${cfg.stateDir} ''; serviceConfig = { ExecStart = "${cfg.package}/bin/nginx -c ${configFile}; }; }; |

Inputs:

- cfg.stateDir: Declared configuration where nginx should store state

- cfg.user: User under which nginx should run

- cfg.group: Group under which nginx should run

- cfg.package: Nginx package to use.

configFile: Generatednginx.confbased on cfg.appendConfig

If any of these inputs change, our nginx is restarted. No code needed to be written.

Example: configure our nginx to build with rtmp support

1 | services.nginx.package = pkgs.nginx.override { rtmp = true; }; |

Input instruction to package nginx has changed, it will be recompiled. $PREFIX path to nginx package returned by function pkgs.nginx.override

will change from something like /nix/store/87428fc522803d31065e7bce3cf03fe475096631e5e07bbd7a0fde60c4cf25c7-nginx-1.4.5 to

/nix/store/0263829989b6fd954f72baaf2fc64bc2e2f01d692d4de72986ea808f6e99813f-nginx-1.4.5 and thus ${cfg.package} will contain a new path,

changing value of an input parameter to systemd service declaration.

Excited? Go install NixOS.

What about Docker?

Docker tries to achieve deterministic builds by isolating your service, building it from a snapshotted OS and running imperative steps on top of it.

Is that the future of Linux configuration management and packaging? I certainly hope not. It's useful for many things, but I don't imagine you'll run your desktop this way.

Stay calm, provision Docker images with Nix

Will more distributions go for stateless design in the future?

- PS: See also previous blog post: Getting started with Nix package manager

- PS2: See my talk on NixOS at FOSDEM . slides